February 2024 Newsletter

Showing Up: Why Freedom Reads’ Work Matters

There are more than 800 pillars, large corten steel monuments that seemingly hang from the sky at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The monuments are memorials. The Oxford English Dictionary says the etymology, a fancy way to say word origin, of memorial is the Latin memoriālis, an adjective for records or the French memorial, an adjective for commemorative, remembered. In this country, there are more things that we would rather forget than remember. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is about remembering. And so, each pillar has the name of a county in America where a lynching has occurred, each has the names, when known, of people who were lynched in this country.

On February 3, I was there with 16 members of the Freedom Reads team. We’d just experienced The Legacy Museum. And I walked onto the six acres of land that holds those hundreds of pillars thinking of all that Black people in this country are enduring.

I do not know what acres my ancestors were shackled nor where they hoofed it when freedom came. My father gave me his surname, but the eighties robbed us, or robbed him of his ability to pass on a history to me. And so, I do not know my grandfather’s given names. And so, I was not looking for them as I walked through the pillars. And so, I was humbled and distracted and distraught and I still do not understand how in five minutes I found my surname, Betts, on two pillars representing counties in Mississippi.

We all know what Faulkner said about the past. Same thing some of us said: I’m a let it go when his name is on the other side of the dirt. And we forget what Morrison said: To fly you gotta let go of all the shit holding you down. And it all comes together at the memorial, at least it did for me. The past, suddenly not the past. But returning in a way that humbled me because I was on the grounds for the work I do: inspire and bring hope to the lives of people incarcerated. And humbled because all day I’d been walking around with these two dual injustices: America’s treatment of Black folks AND the treatment of the lives of people in prison in America. And I wanted to be affirmed in recognizing all the injustice that I’d been fighting.

But my name on the pillar reminded me of a pistol in my hands. It reminded me of the lives of my friends and how we’re all reckoning with this question of what does it mean to be forgiven? What does it mean to be granted mercy in the face of the violence of your own hands. My friends and I have wanted to find some redemption or opportunity in this world despite what we’ve done. And I realized that in some way, I have more in common, or at least some very important thing in common with the people who have done the lynching: in the worst way, we need a mercy that allows possibility and not disaster to flow from accounting for what happened. And maybe that’s how you let it go, without pretending it’s a relic. And maybe this is why, at least for a moment, I walked from those pillars without weeping.

The etymology of memorial also traces it back to the Anglo-Norman, where the word was exclusively meant to mean reminder and the Italian where it meant historical record. This work, ultimately, is our reminder and our historical record. It is the evidence of why this work matters and why the lives of people on the inside matter.

—Reginald Dwayne Betts, Freedom Reads Founder & CEO

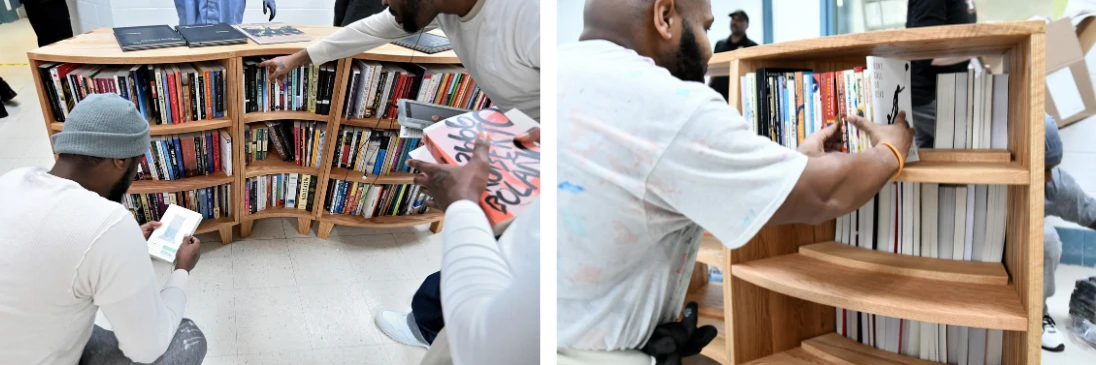

Freedom Reads opened 14 Freedom Libraries this month across three youth and adult detention and correctional facilities in Maryland. The team opened six libraries in Cheltenham Youth Detention Center, four at the Charles H. Hickey, Jr. School, and four additional libraries at Dorsey Run Correctional Facility.

Plus, we were accompanied by our partner Literature to Life, who gave performances of The Giver, adapted from Lois Lowry’s Newbery-Award winning and bestselling novel, at three Maryland youth detention facilities.

Freedom Reads put on literary events at Rhode Island prisons for the first time last week. Freedom Reads Founder & CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts performed his one-man show, FELON: An American Washi Tale. Following the show, Dwayne and Freedom Reads Program Coordinator Steven Parkhurst, who served over 26 years at Rhode Island’s Adult Correctional Institution (ACI), had a wide-ranging conversation about the experience of incarceration and the importance of literature and literary events in transforming the lives of incarcerated people.

From Steven: Exactly five years had passed since I was released from the Rhode Island ACI to serve the remainder of my sentences in Connecticut. The correctional officers who had watched me age on the Inside, eight hour shifts at a time, greeted me at both the men’s and women’s facilities with, “Hey, glad to see you are doing good.” But, the moments that were the hardest were seeing the men at Medium Security go back to their cells when I was free to walk out the front door. I grew up alongside them, most of us teenagers when we met. Now over three decades have elapsed, with less hair and a ton of grays as evidence of our time served.

The men and women had signed copies of Dwayne’s book, Felon, and memories of one of their own showing back up the way Freedom Reads shows up in prisons around the country to do the work we do around books that build community and change lives.

I take photos, like the one above, beside a Department of Corrections sign outside the razor wire and without a prison issued uniform and handcuffs at every prison I visit with Freedom Reads. I take them, both because I can, and to honor the 30 years spent looking out cell windows at freedom.

Last week, Freedom Reads Founder & CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts sat down with Spectrum News NY1’s Annika Pergament to discuss the origin and mission of Freedom Reads, and how one book slid under his cell door in solitary confinement (Dudley Randall’s The Black Poets) changed the trajectory of his life. Earlier this week, Dwayne spoke with WGBH’s Jared Bowen, host of The Culture Show, about access to literature in prison and how books inspire, fuel conversation, and create shared experience.

Plus, earlier this month, Spectrum News Hudson Valley reporter Brooke Reilly chatted with Freedom Reads library patrons Erik Holman and Michael Avallone about the impact Freedom Reads has had on life inside at Otisville Correctional Facility in New York. And, at the top of the month, Dwayne spoke with WBUR’s Simón Rios about access to literature in Massachusetts prisons, the 500-book Freedom Library collection, and the Inside Literary Prize.

Prison Journalism Project and the Florida chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists are seeking nationwide entries for the first annual SPJ-PJP Stillwater Prison Journalism Award, honoring journalistic excellence in the incarcerated community for work published in 2023 across the following categories: Prison Publication of the Year, New Prison Publication of the Year, Prison Journalist of the Year, Most Impactful Journalism, Best News Story, Best Collaboration, Best Feature, Best Op-ed, and Best Illustration.

Each newsletter we aim to share at least one letter (or excerpt) from one of Freedom Reads now 25,000-plus Freedom Library patrons. Freedom Reads receives many letters from the inside. They mean so much to us. And we respond to each and every one of them.

I continue to find new gems on the book shelves, so thank you. I think I’ve read about 20 so far. The shelves had an unintended extra benefit too! Now that our building has a place for books, many books that would normally be tossed anywhere or lost entirely are finding their way to the shelves also (ones not provided by Freedom Reads). So that’s cool :)

– Cameron, Freedom Library Patron in California

None of our work would be possible without your support. Thank you for your generous donations!

We hope you’ll continue supporting us in our mission to open Freedom Libraries in every cellblock across the country.