October 2023 Newsletter

Catching Up with Freedom Reads

Not too long ago, the Freedom Library was but an idea. A dream under development. My entire life had been spent thinking about prison: in poetry, in essays, when I had to explain to my son what it meant to be in prison. But as much as I’d thought about prison, I’d spent little time thinking of what it would have meant to have been able to read Shakespeare before being required to by Professor Sandy Mack years after prison. When asked how I might make the most difference in addressing all the suffering caused by prisons and incarceration, I thought of what saved me: books.

Where others might see only suffering, I knew we wanted to see need and possibility. And so, I thought, what represents the balance of need and possibility necessary to find joy and hope in prison? A library. There are few places more starving for the community that is a library. We bring in beautiful, handcrafted bookcases of maple or oak or cherry and with a specially curated collection of 500 books transform cellblocks into Freedom Libraries. And we wanted to bring these libraries to every cellblock in every prison in America. But until we could do one, it was all a dream – even if a bold one.

In November 2021, Freedom Reads opened the first Freedom Library at MCI-Norfolk in Massachusetts — a prison partly known for its library where Malcolm X transformed his life some 75 years ago. Since then, in a thousand dreams coming true, Freedom Reads has opened 192 Freedom Libraries in 33 prisons and juvenile detention facilities across 10 states. Whose dreams? My own. Our team. The hundreds and hundreds of supporters and funders. But also, and most importantly, the people incarcerated in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola; the Baltimore City Juvenile Justice Center; Rikers Island in New York; the Central California Women’s Facility; and, most recently, in the Maine State Prison, that state’s maximum-security prison, to name but a few of the dozens of prisons where our patrons now have access to beauty and the bounty of great literature.

Where are we now? We’ve been busy and have a lot of catching up with you to do. 2023 has been the year of rapid growth. In January, we loaded an eighteen-wheeler with 24 libraries and headed for Salinas Valley, California. We were bringing Freedom Libraries to California’s Correctional Training Facility, once known as Soledad. We entered with Anne Irwin, her mother Marsha Irwin, and her Aunt Elle. The three had never entered before but walked in with our motley crew to help shelve the Freedom Library. As we crouched around the bookcases and split open the boxes of books, I could hear scrapes of a story. “My husband served time here.” “I’ve always loved mystery books.” “A yo, they have books in Spanish here.” Then Marsha placed two books by her late husband John Irwin on the shelf. John Irwin did time at Soledad in the 60s. Five years. What those who know will call a bid. He came home and ended up becoming a well-respected scholar and professor, and ultimately Professor Emeritus at San Francisco State University. He created Project Rebound and was a founding member of Convict Criminology. He never forgot that he got his desire to know the world in a prison where the only pieces of the world that you could touch were in books. Anne had never been inside of Soledad. Nor had his mother. With Freedom Reads, they returned, believing, like we believe, as John believed, that freedom begins with a book.

—Reginald Dwayne Betts, Freedom Reads Founder & CEO

This past summer, Freedom Reads had its very first internship program. As explained in the article linked below, each year the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale and the Yale Club of New Haven select a nonprofit in the community that is doing innovative work to collaborate with for their social innovation internships. This year, they selected Freedom Reads.

Freedom Reads was delighted to be selected and tremendously grateful for the diligent and excellent work performed by these social innovation interns – Meara Brown and Ana Paula Padilla Castellanos. In addition to reviewing and responding to letters to Freedom Reads from incarcerated individuals, Brown and Padilla Castellanos created comprehensive landscape scans diving into the histories, geographies, and policies of state Departments of Corrections. This work has been critical in expanding Freedom Reads’ efforts. The interns were supervised by Freedom Reads Program Manager Claire Elliman and Freedom Reads Program Coordinator Steven Parkhurst. And their presence at Freedom Reads was a joy for the entire organization, and a real benefit to the people Freedom Reads serves.

To quote this piece by Lisa Beebe – How Two Social Innovation Interns Made Their Mark at Freedom Reads, a Startup Nonprofit: “Everyone involved — from Tsai CITY, the Yale Club of New Haven, and Freedom Reads — considers the social innovation internships a resounding success. And the interns themselves? Well, Brown calls her internship ‘life-changing,’ and Padilla Castellanos says she’s ‘insanely grateful’ for the experience.”

We listen to podcasts obsessively. And as much as we love the articles that have been written about Freedom Reads, we’re still a young enough organization that listening to Dwayne talk about our work sounds fresh each time. This one is worth a listen – hosted by New York Times bestselling author and economist Steven Levitt, Dwayne appears on the podcast Freakonomics: Reading Dostoevsky Behind Bars.

Coverage of Freedom Reads’ work in the press continues to expand and deepen. In this section we offer just some of the highlights of recent media coverage.

Of late, Fast Company and Surface Magazine examined the very deliberate design of the Freedom Library. As explained in this piece in Fast Company,

In the carceral world, where design isn’t typically a consideration, Freedom Reads’ libraries are a notable exception. The bookshelves don’t hang on a wall—they sit, hand-built and curved, as locus points inside a facility’s housing units. The libraries have been built into the smaller community rooms where people gather to watch TV or in the center of a dormitory inside an empty cell. Betts describes them as ‘almost like storefront churches.’ The libraries exist in a space where those inside can congregate, becoming what Betts calls ‘an intellectual life blood.’

Surface Magazine, which “covers the worlds of architecture, art, design…with a focus on how these fields shape and are shaped by contemporary culture[,]” assessed that Freedom Reads is “building high-design libraries in prisons” whose “curves intentionally contrast the carceral system’s rigid architecture and echo a Martin Luther King Jr. quote about the arc of the universe bending toward justice.”

Over the summer, Harvard University’s Houghton Library offered a special exhibition exploring writing in prison – “Sentences: Prison Writing through the Ages” – which, as reported by Harvard Magazine, “actively engages with [Reginald Dwayne] Betts’s artistic and moral sensibility.”

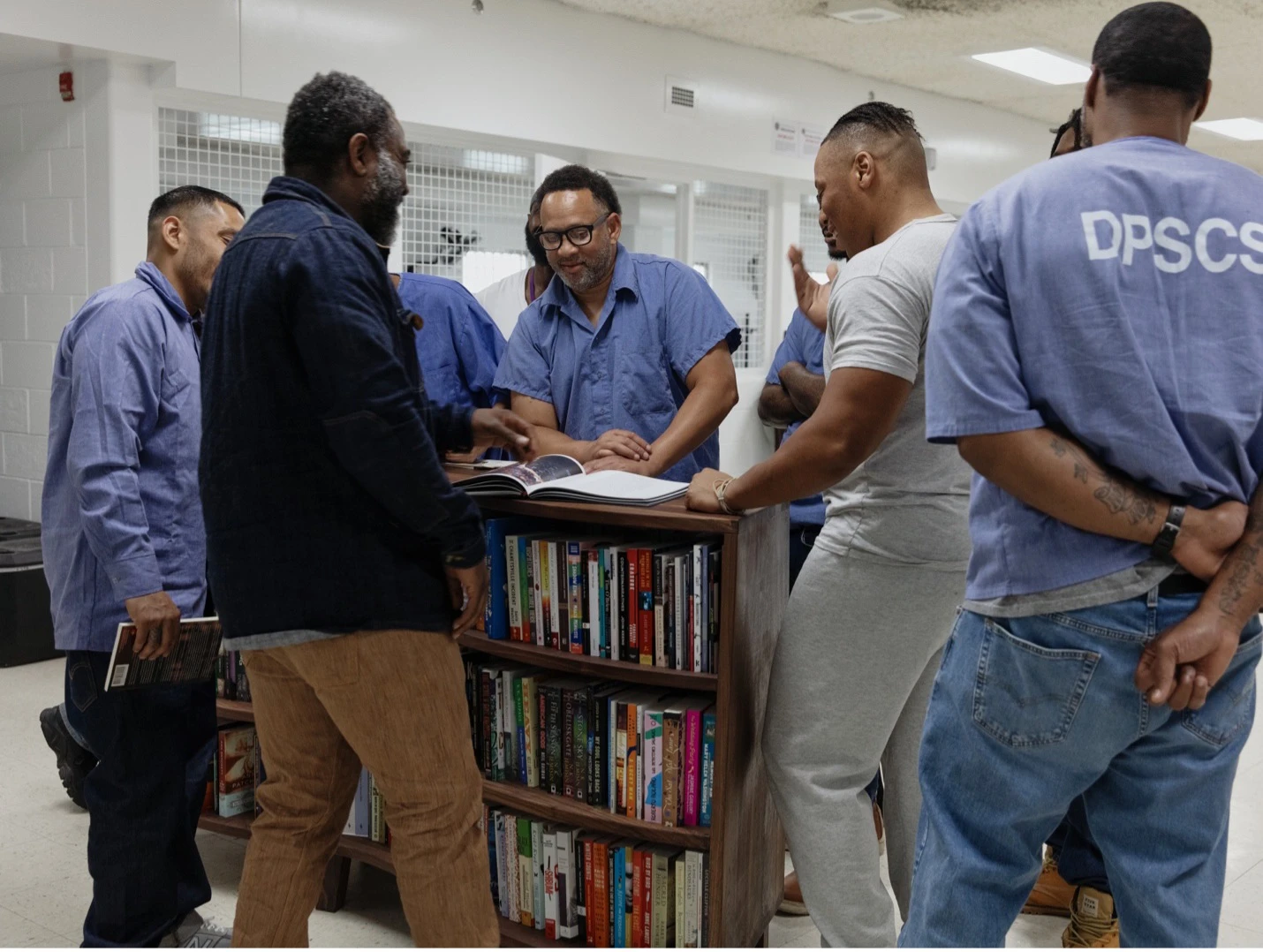

In June, Freedom Reads opened 11 Freedom Libraries at the Baltimore City Juvenile Justice Center, and four more at the Dorsey Run Correctional Facility in Jessup, Maryland. On the day of these Freedom Library openings, Maryland Public Radio (WYPR) aired an interview with Freedom Reads Founder & CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts and Maryland’s Secretary of Juvenile Services Vincent Schiraldi about the openings and how “Books ignite the belief in a positive future.” And the Baltimore Sun sent their photographer to capture the openings at the Baltimore City Juvenile Justice Center, an image Baltimore Sun selected as its picture of the day (scroll down about 10 pictures via this link).

Of course, there is much work that remains to be done. Robert Lee Williams, for example, is an avid reader incarcerated at Sullivan Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in New York. He wrote a piece for Literary Hub that was published a few weeks ago. In it he “muses on access to literature” and talks about the impact of a New York Review of Books interview of Freedom Reads Founder & CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts conducted by John J. Lennon, a published writer incarcerated at Sullivan who is also Galaxy Leader Fellow and Freedom Reads Literary Ambassador. Williams closes the piece with a question, “What if there was a Freedom Reads curated library here?” With your support, we can make it happen.

Freedom can take many forms, writes Charles Baxter in his short piece on Freedom Reads in the Angolite, a magazine edited and published by incarcerated people at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Baxter’s letter is a testament to why we do our work. Incarcerated in 1997, Baxter would serve 26 years in prison. While the dorm I live in is comprised mostly of older prisoners, many with health issues, the books are just as important to them, Baxter writes of the Freedom Library. It’s hard to imagine what it means to spend 26 years in prison for most people, but for those that we work with, for the men and women and even many of the children who we meet when we open Freedom Libraries in cellblocks, the suffering that comes with that kind of time is known. But what’s also known is what many of us do with that time, even while inside. I shall hopefully get to leave Angola, and when I do, one of the things I’m most proud of is being able to help others learn to read, writes Baxter at the end of his article on Freedom Reads. Mr. Baxter did not make it out of Angola, but as a writer his words did and as an educator and a lover of books, we believe that his influence will continue to resonate.

We started believing that one Freedom Library per prison is what was needed to shift the landscape. Then, weeks after we opened a Freedom Library at MCI-Norfolk, a man incarcerated there requested one for his unit. Consistently, the same thing would happen. Witnessing the curving bookcases and the possibility revealed by the titles in our collections, opening one Freedom Library quickly becomes a conversation about opening more. When we visited the Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility in Colorado, the first thing that Warden Mark Fairbairn said to Freedom Reads Founder & CEO was, “I was skeptical at first, but let me show you why we need 17 more Freedom Libraries here.” He then showed Dwayne what a cellblock looks like without one and why such a stark juxtaposition was an injustice. It’s not just prison officials that see need and value. It’s those incarcerated and even their parents. We get many letters. Here is one that reflects the power of the Freedom Library:

Dear Freedom Reads Family,

Today I was filled with excitement, curiosity, inspiration and deep gratitude when a Freedom Reads bookshelf was delivered to our housing unit. And these books are NEW! By amazing authors, some I was familiar with but also new to me. I felt so excited picking up titles, reading the back and feeling the overwhelm being in the company of so many good books. At one point, in our mutual excitement, I locked eyes with a woman I had a conflict with, and after a pause she asked me how I was doing. Just like that weeks of resentment and animosity towards this person evaporated over a shelf of books in the unlikeliest of places. Your project already made a ripple in my life on day 1. Prison is not a place that nurtures inspiration, curiosity or gratitude; and inmates are not given trust. But today I experienced all of the above. So I can tell you honestly that I witnessed the Freedom Reads project transcend prison in a matter of minutes. I am grateful your project exists and has enough energy behind it to make a difference. Your effort matters! This is my first time in prison and everything about it insults my soul. I didn’t know we treated people with such a lack of regard until I came here. I feel called to use my experience in a meaningful way.

Thank you for showing me how!

— Nicole, Freedom Library Patron

As reported by The Marshall Project in this story, “As of July 1, most people in prisons — though not in jails or detention centers — are now eligible to receive Pell Grant student aid, for the first time in nearly 30 years. The Associated Press reports that the change will give an additional 30,000 students behind bars access to some $130 million in financial aid per year. In all, 760,000 incarcerated people could be newly eligible for aid according to the Department of Education, though many prisons don’t yet have capacity or higher education partners.”

By Steven Parkhurst, Freedom Reads Program Coordinator

Tyler Sperrazza, the Chief Production Officer at Freedom Reads, and I pulled our 26-foot Penske moving truck full of Freedom Libraries into the staff parking lot of the Maine Correctional Center, just a couple dozen feet from the sally-port that gave entrance to the prison grounds. We had just driven 240 miles from Hamden, Connecticut, to Windham, Maine, and my heart was pounding.

I had been released from prison 3 ½ months earlier after serving 30 years. I don’t want to say I felt at home pulling up, but prison is the house I grew up in.

We had traveled to the Maine Correctional Center to open Freedom Libraries inside seven different housing units. I felt like I was bringing these men and women the world, the stories that set me free, book after book after book.

I remember the decades’ worth of volunteers visiting my prisons. They brought books, education, stories, joy, and hope. I always felt a little bit of their freedom for those brief moments in time. And here I was, sharing my freedom.

For me now, walking back in, especially through the front door, is the ultimate freedom. No handcuffs, belly chains, or strip searches after signing the visitor’s logbook and receiving a clip-on visitor’s pass. I even used the visitors’ bathroom, not because I needed to, but because I could. But the metal detector still taunted me and the GPS monitor around my ankle felt extra heavy.

Once in the housing unit, I was home. The men and women leapt at the chance to be the first hands on these books. They approached without hesitation and with a familiar energy to help fill the bookshelves. I could see myself in them, scanning the back covers, considering which to take back to the cell, which would be the first to free their mind from prison.

The five hours went by fast. Tyler and I took a few pictures with the prison in the background because who would believe they let me back in, then out again? After less than four months on the outside, I couldn’t, and I felt a twinge of guilt when we pulled onto the road. I got to leave, but the men and women I just met didn’t.

But the now empty truck rumbling behind us reminded me that we didn’t abandon them. Freedom Reads left them with over 3,000 books, each one offering companionship, hope, and a vision for their future outside.

I’ll never forget my first time back.