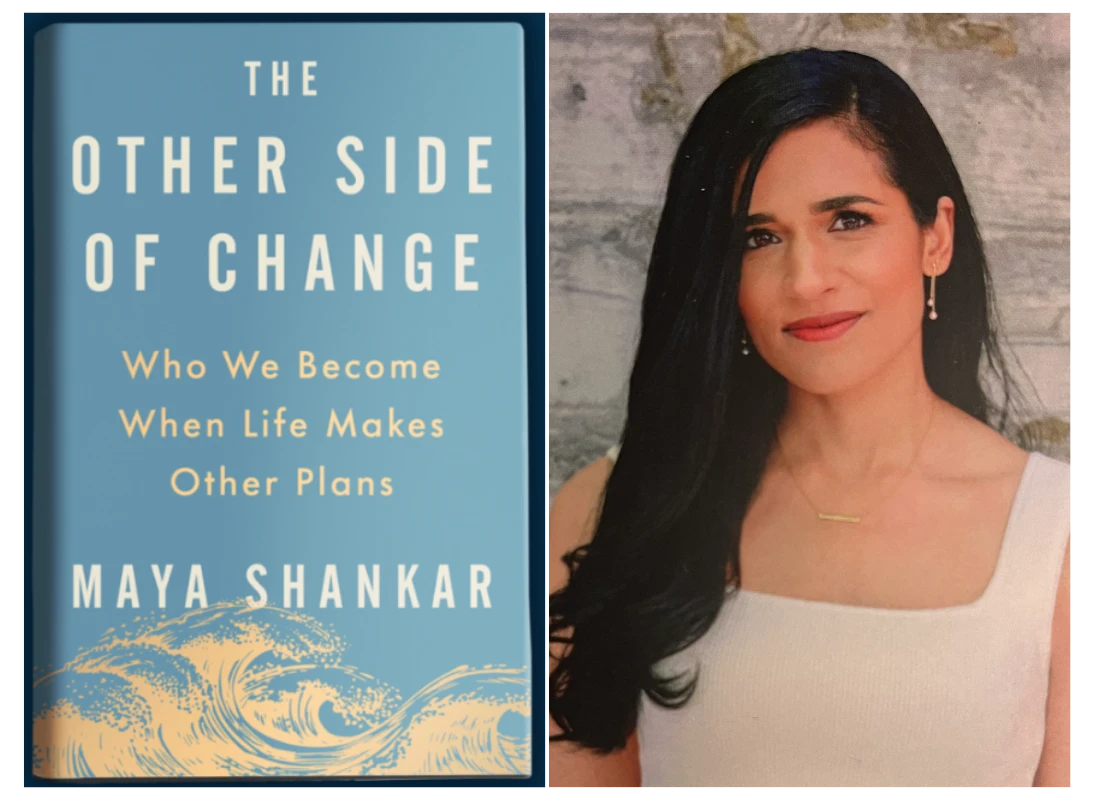

In her outstanding new book The Other Side of Change: Who We Become When Life Makes Other Plans, cognitive scientist and podcaster, Maya Shankar takes a refreshing look at how the typically unsettling process of change can be seen as an opportunity. Change can be frightening and disorienting, but it can also be transformative. Drawing on stories of people who underwent life-altering personal change, including Freedom Reads founder and CEO, Dwayne Betts, the book focuses the reader’s attention on what is possible following reality-changing events. Here is a short excerpt from the chapter entitled “Possible Selves.”

.....................................................................................................................................................

Dwayne was released from prison in 2005 at the age of twenty-four, roughly a year after he published his first poem. Since he’d earned his high school diploma while incarcerated, he was able to enroll in Prince George’s Community College in Maryland. He also got a job at Karibu Books, an independent bookstore, where he started the YoungMenRead book club for Black kids in the community. He then went on to earn a BA from the University of Maryland, an MFA in creative writing from Warren Wilson College in North Carolina, and a law degree from Yale. In 2009, he published A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison, which he followed with several poetry collections, including Bastards of the Reagan Era and Felon. In 2012, President Barack Obama appointed him to a task force on restoring juvenile justice and preventing delinquency. Dwayne was told he was the first-ever formerly incarcerated person to receive such an appointment.

But his criminal record has followed him throughout these experiences. Dwayne applied to Howard University after his second year in community college and was accepted on a full scholarship, but he said that it fell through once he revealed that he’d been incarcerated. After he graduated from Yale Law School and passed the bar exam, the Connecticut Bar Association sent him a letter saying that he would need to prove his “character and fitness” to practice as an attorney, due to his time in prison. Dwayne cried when he received the letter. (He pulled together recommendations from professors and former prisoners and was eventually sworn in as an attorney at a courthouse in New Haven.) At times, he has struggled to get job offers or approval to rent apartments. When he went on a second date with his future [and now ex]wife, he worried that disclosing his past might end their budding romance. His prison sentence was not just something he carried in the world—it was something everyone he loved would need to carry too.

And yet Dwayne has found more richness both inside and outside his identity as a former prisoner than he could have imagined. He remains committed to supporting his friends who are still incarcerated, and as their lawyer, he’s helped many of them secure early parole. My conversations with him were frequently interrupted by calls from prison, which he always accepted. In 2020, he created a nonprofit called Freedom Reads, which builds small libraries in prisons, juvenile facilities, and immigrant detention centers across the United States. The libraries’ books, which range from Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to Andre Agassi’s memoir, are placed on shelves carved from walnut, maple, and cherry wood, an intentional design choice meant to counteract the bleakness of prison. There are now more than four hundred libraries in nearly fifty institutions. [As of today, there are 605 Freedom Libraries in 60 correctional facilities]. One superintendent who’d worked in the system for decades told Dwayne that he was eager to participate in the library project because he had never come across anything beautiful inside of a prison. In 2021, Dwayne was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, informally known as the “Genius Grant.”

…

Writing has been a way for Dwayne to process both the atrocities and the humanity he observed while in prison. He feels compelled to share his stories as a means of honoring the people he’s met along the way, especially those who still remain behind bars. “Poetry,” he said, “is a medium of caring.”

In his poems, Dwayne often uses an interesting device: he writes in the first person, even when he’s writing about something he himself has never experienced. “I barely see my daughters at all these days. / Out here caught up, lost in an old cliché,” he writes in one poem, though Dwayne has been a devoted and present father to his two young sons. He does this because he believes that if he implicates himself in society’s ills, then he—and his readers—will feel responsible for finding solutions. It’s a way of advocating for people whose stories merit empathy and attention. “When you read a poem out loud in the first person, in all the uncomfortable imagining, the line blurs between you and them,” he said.

Excerpted from THE OTHER SIDE OF CHANGE by Maya Shankar. Copyright © 2026 by Maya Shankar. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.